Beauty is truly in the eyes of the beholder, but there are a few who win the vote almost unanimously. Those whose beauty is simply undeniable. They transcend size, height, ethnicity, complexion and with enough notoriety, even time. They may not fit your personal idea of what you find attractive but chances are, a part of you gets “what all the fuss is about.”

In recent days, I completed a quick survey, in which I asked 342 black persons of varying decent, gender and ethnicity:

1)Have you heard the term “what a beautiful/pretty black girl?”

2)Was the person of color or Caucasian?

All 342, who also fell between the ages of 28-41, reported that they have heard the expression. 264 persons stated they heard/hear this term most often from black persons. 28 reported that they have heard the term said by both blacks and whites, and the remaining 50 stated they heard the expression from Caucasians only.

The expression, “what a beautiful black girl” has always rubbed me the wrong way, especially when I hear older black women say it. Not because I think it’s a hateful comment but because it highlights and continues to perpetuate a divide. It brings to the forefront a psychological oppression that’s deeply ingrained in many people. The notion that darker is lesser. I’ve yet to hear anyone say, “what a beautiful white girl.” Even reading it out loud just doesn’t sound right. I have however, heard the term interchanged with different ethnicities (What a beautiful Asian girl for instance).

So why the extra adjectives? Why is the expression so commonly uttered?

Perhaps the answers aren’t as important as the fact that we should desist from saying it altogether. Not because it’s an overtly racist thing to say, but because it’s a nonsensical term that adds to that “us” and “them” stigma. It also adds to a self-fulfilling prophecy when black person believe it’s a perfectly harmless thing to say to dark-skinned girls. It infers that being dark(not just black) and pretty is different from being Asian and pretty, Indian and pretty or White and pretty. There are enough stigmas surrounding generalized ideas of beauty that augment the self-esteem issues so many women have today. Subliminally suggesting to a dark-skinned girl who black beauty is in a way so separate or uncommon, can be all the more demoralizing.

Conversations surrounding “colonialism, white supremacy, and the fact that racism persists today” provide some rationale for this behavior. For the most part, most of us can concede to the marring of a people’s psyche and the influences this has had on many generations. Not withstanding this, it doesn’t mean the behavior doesn’t persist within our own community and it doesn’t impact the fact that we ourselves should not be doing it. Many subtle acts of “racism” aren’t rendered from hateful prejudice but from sheer ignorance. Many persons (black and white) don’t even interpret the description “beautiful black girl” as offensive. In fact, it can also be said that when uttered by those of color, the term is more aligned with issues of colorism. A plight of perpetuated prejudice seen within our own racial group. A plight, in which darker persons within the same racial class exalt those of a lighter complexion. Pigmentocracy and other issues of colorism could be expanded upon for days but those socioeconomic structures are not as modifiable as our own marred perceptions of beauty.

So often we separate ourselves from ourselves. Those who lighten their skin with bleaching agents are consistently berated by those who add chemicals to straighten or loosen their curls. One could easily argue that these decisions are driven by the same notions. The texture of a colored woman’s hair is not bone straight. Does that mean the decision to straighten or weave ones hair mirrors the same accused attempt to be closer to those of a lighter complexion? We become so impressed with persons who uphold their natural physique. We publish articles heralding black women for keeping their natural curls, as though it is some form of accomplishment. The truth is, it actually is. It’s not common to find dark-skinned women with natural hair. But does that make you less black? Are you straightening your hair in an attempt to fit in with other races. I’m going to go out on a limb and guess no. For most persons, it’s just a way of styling your hair, or as most would admit making it more manageable.

When I asked a young man the aforementioned survey questions, he conceded to being one of the black persons who’s used the expression. He added, that in a way he found the term relevant and has used it across different ethnicities. When I asked, “how could it be relevant?” He answered, “You know, when you see a woman, that literally and unmistakably typifies the stereotypical physical features of her race or ethnic heritage, and it’s as if it’s those striking genetic features that make her fascinatingly gorgeous.” I thought for a moment then replied, “I sort of do.”

The Formula

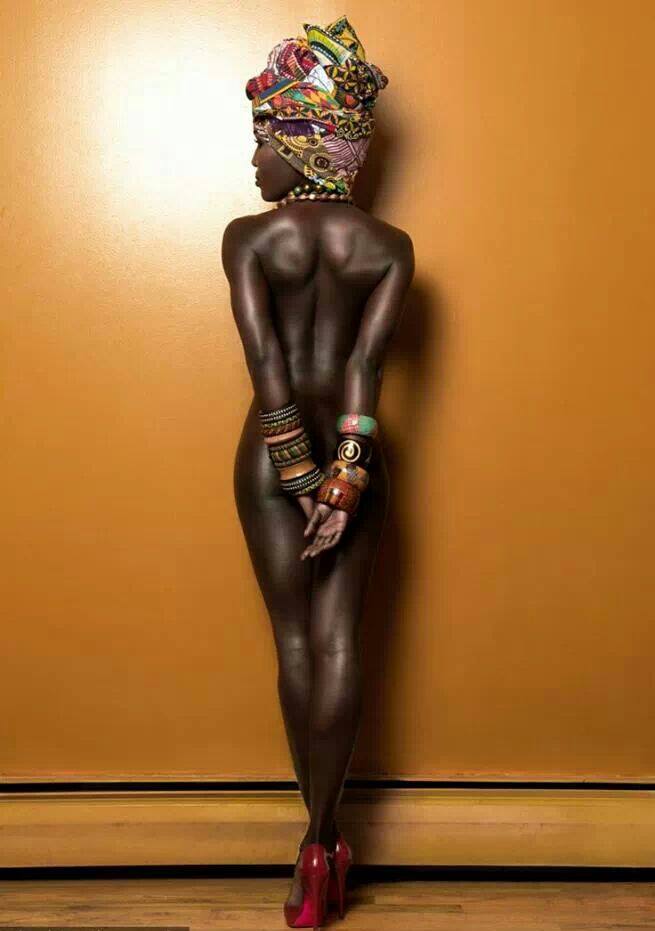

Context plays a major role in any communicative exchange. Often, due to our past experiences and the similarities a present instance shares with that past, we rob ourselves of insight. Our immediate unease and the safety that comes with the willingness to believe that if it walks like a duck, then it must be one, denies us the opportunity to see things in a different light. While I am still not a fan of the term and remain vigilant about my preference that we stop using it altogether, I can appreciate that it may often come from a place of ignorance, or even a place of sincere admiration. I can see how a woman with very dark skin, untouched hair, full ripened lips and voluptuous curves can be fittingly described as a “beautiful black woman.” On the other hand, any term that further adds to categorizing any individual, further adds to separating said individual. Lets not to do it. Beautiful is complement enough.

Featured Image is courtesy of DuJour Magazine retrieved from OOTD Magazine

Jacqui

July 19, 2015 at 10:42 pm (9 years ago)” I remember her as a little girl; she was dark but she was pretty.” That’s the comment an aunt of mine made to my father’s wife while we were both visiting her in the hospital. I was shocked because it was the first time in my life that she had ever referred to me as pretty.

I grew up knowing that I was not beautiful or pretty because I was always referred to as “the little dark one” while I constantly heard everyone talk about how pretty my sister’s skin was and how much she looked like our beautiful mother, who was also very light skinned.

I’m sorry to say that in my experience, the idea of someone being pretty in spite of their dark skin, is a thought that has been perpetuated by my own race. “What a beautiful/pretty black girl”, I heard it many times and whenever I have, it has been by blacks and what is meant is that the girll is beautiful in spite of her blackness. Sad but true.